Do Correctional Facilities Required To Provide Health Services To Incarcerated Individuals?

Introduction

Individuals transitioning into and out of the criminal justice system include many low-income adults with significant physical and mental wellness needs who face up a variety of economic and social challenges. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) coverage expansions, especially the Medicaid expansion, provide new opportunities to increase health coverage for this population, which may contribute to improvements in their ability to access care as well every bit greater stability in their lives and reduced recidivism rates. This brief provides an overview of the adult criminal justice-involved population and the potential impacts of the ACA on their health coverage. (For information on health coverage and care for youth in the juvenile justice system, run into: https://world wide web.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/health-coverage-and-care-for-youth-in-the-juvenile-justice-arrangement-the-role-of-medicaid-and-chip/.)

The Criminal Justice Organisation

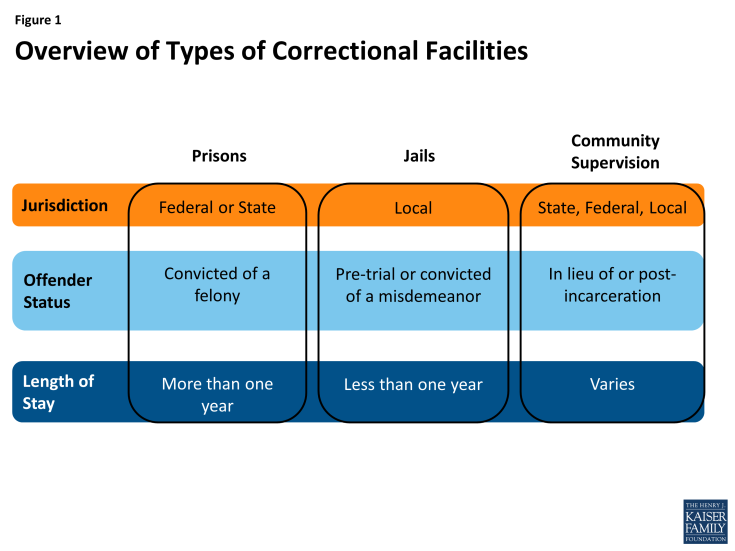

Figure 1: Overview of Types of Correctional Facilities

The criminal justice system is comprised of a range of unlike types of correctional facilities (Figure ane). Correctional facilities include prisons, which typically house longer-term felons or inmates serving a sentence of more than than one year, and jails, which business firm individuals awaiting trial or sentencing and those convicted of misdemeanors and serving shorter terms that are typically less than i twelvemonth. In that location as well are several forms of community-based corrections, including probation, parole, and halfway houses. Offenders in community corrections frequently are required to adhere to strict conditions and rules, and failure to comply with these requirements may lead to incarceration or re-incarceration.

Prisons are overseen past the federal government and states, while jails typically are governed past the local metropolis or county. The federal correctional system consists of prisons overseen by the Federal Bureau of Prisons, which house individuals convicted of a federal crime and generally serving a term of more than than one year. State correctional systems oversee prisons housing individuals convicted of land crimes and mostly serving terms of more than ane year. Each land governs its own prison organization through a Section of Corrections. In that location are over 3,200 jails nationwide housing individuals awaiting trial or serving a short sentence for a misdemeanor, with almost counties (2,977 out of 3,069) operating their ain jails.i

The Criminal Justice-Involved Population

Nigh 2.3 million individuals are incarcerated in prison or jail, only millions more than collaborate with the correctional arrangement annually (Table one). (Encounter Appendix Tabular array 1 for data by state.) About 1.5 1000000 individuals were incarcerated in prisons as of the end of 2012. Over the course of the yr, about 600,000 individuals are admitted to prison and a like number are released.2 As of mid-twelvemonth 2013, over 730,000 individuals were in jails.3 About half-dozen in ten of these individuals were not convicted and awaiting court action; the remaining four in ten were sentenced or bedevilled offenders awaiting sentencing.4 Given the shorter terms of jail inmates compared to prisoners, there is rapid churn amid the jail population. Between July 2012 and June 2013, an estimated 11.7 million people were admitted to local jails and, on boilerplate, jails experienced a weekly turnover rate of 60%.5 The jail population is concentrated in large jails (that have an average daily population of 1,000 or more than inmates), which house nearly half (48%) of all jail inmates but simply business relationship for 6% of all jail jurisdictions.6 An additional 4.8 1000000 adults were under community supervision as of the stop of 2012, and nigh four.one million adults entered and exited community supervision over the course of 2012.7 About 80% of adults under customs supervision are on probation, while the remainder is on parole.

| Tabular array ane: Overview of the Criminal Justice Involved Population | |

| Prisoners | |

| Number of Prisoners as of December 31, 2012 | 1,570,397 |

| Number of Admissions of Sentenced Prisoners during 2012 | 609,781 |

| Number of Releases of Sentenced Prisoners during 2012 | 637,411 |

| Jail Inmates | |

| Number of Inmates in Local Jails as of June 2013 | 731,208 |

| Number of Persons Admitted to Local Jails, July 2012-June 2013 | 11,700,000 |

| Weekly Turnover Rate, calendar week catastrophe June thirty, 2013 | lx% |

| Adults Under Customs Supervision | |

| Number Under Community Supervision as of December 31, 2012 | 4,781,300 |

| Number Inbound Community Supervision during 2012 | ii,544,400 |

| Number Exiting Customs Supervision during 2012 | two,585,900 |

| Sources: Agency of Justice Statistics, Prisoners in 2012, Trends in Admissions and Releases, 1991-2012, U.S. Department of Justice, December 2013; Bureau of Justice Statistics, Jail Inmates at Midyear 2013 Statistical Tables, U.South. Department of Justice, May 2014, and Bureau of Justice Statistics, Probation and Parole in the United Country, 2012, U.S. Section of Justice, Revised April 22, 2014. See sources for methodology and notes. | |

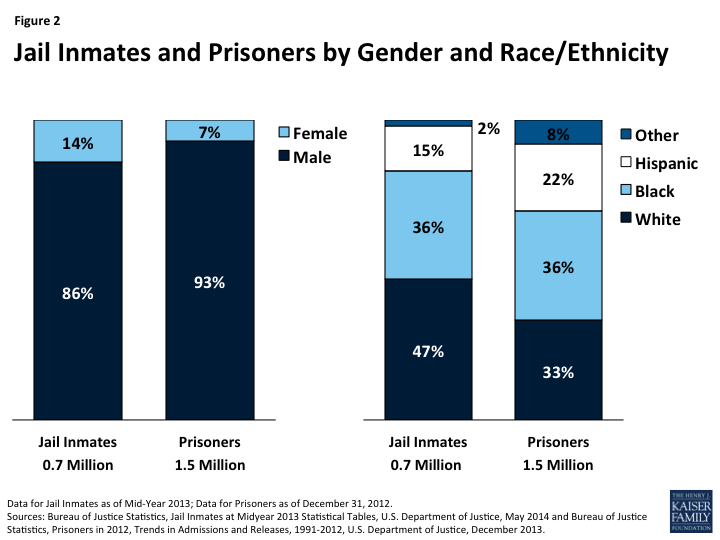

Adult males of color brand upwards the majority of the incarcerated population. As of 2013, 99% of jail inmates were adults and 86% were male. Only over half of the jail population (53%) was people of color, including more than than a third who were Black (36%) and fifteen% who were Hispanic (Figure 2).8 Amongst prisoners, more than nine in 10 are male (93%) and two-thirds (66%) are people of color.9 These patterns reflect college incarceration rates among people of color compared to Whites. Incarceration rates for Black men are over 6 times higher than the rate for White men and almost two and one-half times college than the charge per unit for Hispanic men.10 American Indians as well have higher rates of incarceration compared to Whites.11

Figure 2: Jail Inmates and Prisoners past Gender and Race/Ethnicity

People involved with the criminal justice system are mostly low-income and uninsured. Overall, data on the income and insurance status of people moving into and out of the criminal justice organisation are express. However, survey data from 2002 show that nearly half dozen in ten jail inmates reported monthly income of less than $1,000 prior to their arrest.12 Data also suggest that the population is largely uninsured. For example, a survey of San Francisco county jails plant that nigh xc% of people who enter county jails have no health insurance.13 Another survey of inmates returning to the customs from Illinois jails found that more than than viii in ten were uninsured after returning to the community at 16 months mail-release.14

The incarcerated population has meaning concrete and mental health needs. Chronic illness is prevalent among the population with higher rates of tuberculosis, HIV, Hepatitis B and C, arthritis, diabetes, and sexually transmitted disease compared to the general population.15 Over half of prison and jail inmates have a mental wellness disorder, with local jail inmates experiencing the highest rate (64%).16 These disorders include mania, major depression, and psychotic disorders.17 Prisoners and jail inmates who have a mental health disorder are more likely than those without a disorder to have been homeless in the twelvemonth prior to their incarceration, less probable to have been employed prior to their arrest, and more probable to report a history of concrete or sexual abuse. Moreover, the majority of inmates with a mental health disorder also take a substance or alcohol use disorder.xviii

Individuals moving into and out of the criminal justice organization as well face a multifariousness of social challenges. Poverty, unemployment, lower teaching levels, housing instability, and homelessness are all more prevalent bug amongst criminal justice-involved population than the full general population.19 This population also generally has college rates of learning disabilities and lower rates of literacy.xx

Health Care for Incarcerated Individuals

Correctional facilities are required to provide health services to incarcerated individuals, only many inmates go without needed care. The provision of health intendance varies significantly across states and types of correctional facilities. Some larger prisons have infirmaries on-site, and many prisons rent independent doctors or contract with private or hospital staff to provide care, with the majority of prisons creating a hybrid system. In jails, health care is primarily provided through contracts with local health care providers, such every bit public hospitals or other safety-net providers, who come to the jails to provide services. Every bit with big prisons, some large jails have on-site primary care, pharmacy, and mental health and substance abuse centers. Even though these services are bachelor, information prove that many inmates go without needed health care while incarcerated. For example, a 2009 written report plant that, among inmates with a persistent medical trouble, approximately 14% of federal inmates, 20% of country inmates, and 68% of local jail inmates did non receive a medical examination while incarcerated.21 Near two thirds of prison inmates and less than half of jail inmates who had previously been treated with a psychiatric medication had taken medication for a mental condition since incarceration.22

States have been facing rising costs in prison health care spending. Every bit of 2011, state spending on correctional health intendance was about $7.7 billion, accounting for nearly a fifth of total prison expenditures.23 Betwixt 2007 and 2011, correctional wellness care spending rose in 41 states, with a median growth rate of 13 percentage.24 This growth reflects a combination of an increase in the prison population and higher per-inmate expenses due to an crumbling inmate population, the prevalence of physical and mental health needs, and challenges in delivering wellness care in prisons, such as distances from hospitals and providers.25 All the same, in most states, spending peaked before fiscal year 2011 and has been declining since so due, in office, to a reduction in state prison house populations.26

Medicaid has historically played a very limited part in roofing inmate health care costs. Prior to the ACA, Medicaid eligibility was express to low-income people who fell into certain groups, including children, pregnant women, parents of dependent children, and elderly and disabled adults. Overall, eligibility for non-disabled, non-elderly adults was very limited, with adults without dependent children mostly excluded from the program and income eligibility limits for parents remaining very low in nigh states.27 As such, many inmates historically could not authorize for Medicaid since they did not fit into i of the chiselled eligibility categories. Even for inmates who practice qualify for Medicaid, federal law prohibits Medicaid payment for near wellness care services provided to individuals while incarcerated under a policy known as the "inmate exclusion" (meet Box one). Given these limitations, previously, few states pursued Medicaid financing for eligible prisoners' wellness care services.28

Box one: The Medicaid Inmate Exclusion Policy

.

Federal Medicaid police prohibits the payment of federal Medicaid matching funds for the cost of whatsoever services provided to an "inmate of a public establishment," except when the individual is a "patient in a medical institution."29

.

This policy applies to both adults in jails or prisons besides equally to youth involuntarily detained in a state or local juvenile facility.This policy does not prohibit individuals from being enrolled in Medicaid while incarcerated; however, even if they are enrolled, Medicaid volition not cover the cost of their care, except for care received as an inpatient in a infirmary or other medical institution.

.

Considering individuals may remain enrolled, states can suspend, rather than finish, Medicaid coverage for inmates to accommodate the inmate exclusion. However, break and termination policies vary across states.

The ACA and the Criminal Justice-Involved Population

The ACA offers new opportunities to increase wellness coverage amidst individuals transitioning back into the community from prisons and jails. The ACA established new coverage options by expanding Medicaid eligibility to nearly all adults with incomes at or beneath 138% FPL ($16,105 for an individual in 2014). The federal government will comprehend 100% of the cost of coverage for individuals fabricated newly eligible every bit a result of this expansion, phasing downwardly to a 90% federal match as of 2020. The ACA also created new Health Insurance Marketplaces with premium tax credits available for moderate income individuals. In add-on to these coverage expansions, the ACA also requires all states to implement streamlined, coordinated enrollment processes to connect eligible individuals to health coverage.

The ACA coverage expansions provide new coverage options for many individuals who interact with the criminal justice system. Although as enacted in the ACA, the Medicaid expansion would occur in all states, the Supreme Court ruling on the ACA effectively fabricated the expansion a state option. Every bit of Baronial 2014, 28 states are implementing the expansion.30 In states expanding Medicaid to low-income adults, many individuals who interact with the criminal justice system are newly eligible for the program. Moreover, in all states, some individuals beingness released from prison house and jail may qualify for coverage under the new Marketplaces established by the ACA (encounter Box 2). All the same, in states not implementing the Medicaid expansion, many poor uninsured adults did not gain a new coverage option and will likely remain uninsured. While the coverage expansions increase coverage options for individuals transitioning through the criminal justice system, targeted outreach and enrollment efforts will be fundamental for translating these new options into increased coverage, particularly since the population faces a wide range of enrollment barriers such as lack of knowledge almost coverage options and lower literacy and education levels.31

Box 2: Medicaid and Marketplace Enrollment Policies for Incarcerated Individuals

.

Medicaid. Individuals incarcerated in jail or prison may enroll in Medicaid while incarcerated. However, Medicaid volition not pay for most medical intendance for individuals while they are housed in jail or prison house due to the federal inmate exclusion policy.

.

Marketplace coverage. Individuals may not purchase coverage through the Marketplace while serving a term in prison or jail. (This bar on purchasing coverage does not extend to individuals in jail or prison who are pending disposition of charges—i.e., being held merely not notwithstanding convicted of a crime.) Individuals are provided a 60-day special enrollment period that begins upon belch from jail or prison house. During this time, they may enroll in coverage even if it is outside the Market place open up enrollment period. However, because this special enrollment menstruum does not brainstorm until the time of release, they volition likely experience a gap in coverage between the time of discharge and completion of enrollment in coverage. Later the lx-day special enrollment period, individuals are non eligible to purchase coverage through the Marketplace until the side by side regular open enrollment menses or unless they authorize for a different special enrollment period.

.

Source: "Wellness coverage for incarcerated people," at https://www.healthcare.gov/incarceration/

Correctional facilities can play a key role in connecting eligible individuals to coverage and care to facilitate their reintegration back into the customs. Correctional facilities can assist connect eligible individuals to coverage by providing outreach and educational activity nearly coverage options every bit well as direct enrollment help either through staff or by bringing in external enrollment assisters. Providing this assistance within jails may be challenging since at that place is oftentimes limited time to connect individuals with resource or support community re-entry given the curt-terms of jail inmates. However, several states and localities have already launched initiatives to enroll individuals into coverage and facilitate connections to community providers as individuals transition back into the community (meet Box iii).

Increased coverage amidst the criminal justice-involved population may lead to improved access to care and broader benefits, including reduced backsliding rates. Equally noted, individuals transitioning into and out of prisons and jails have significant physical and mental health needs. Upon release from prison and jail, individuals are frequently uninsured, making it difficult to access stable sources of care in the customs to accost these needs. Expanding wellness insurance to these individuals volition likely facilitate their power to admission needed intendance and manage their ongoing weather condition. Improved connections to services and better management of health conditions may likewise contribute to reduced rates of recidivism, particularly among individuals with mental wellness and substance abuse disorders. For example, in Michigan, rates of backsliding fell post-obit implementation of an initiative that links newly released prisoners to a medical dwelling house in the community, helps them access needed medications and master and specialty care, and assists them in obtaining their medical records upon release.32 In add-on, studies in Florida and Washington found that people with severe mental illness who were enrolled in Medicaid at jail release were more probable to access community mental health and substance corruption services than those without Medicaid, and that 12 months after release, Medicaid enrollees had 16% fewer detentions and stayed out of jail longer than those who either were not enrolled or had been enrolled for a shorter time.33

Box 3: Connecting Individuals to Coverage and Care to Support Community Re-Entry

.

Awarding Assistance in Cook County Jail. Cook County Wellness and Hospital Organization (CCHHS) partnered with Cook Canton Sheriff'due south Part (CCSO) and a non-profit organization, Treatment Alternatives for Safe Communities (TASC), to screen detainees entering Melt Canton Jail for eligibility for CountyCare, the county's Medicaid expansion programme. By using information gathered at intake, TASC employees are able to validate identity and meet application requirements onsite. As of April i, 2014, approximately 3,845 people received coverage after starting an awarding in jail and at that place is a 94% blessing rate for applications submitted from Cook Canton Jail.34

.

Connections Correctional Health Care Services in Delaware. Connections is a customs based not-for-profit organization that provides behavioral health intendance in all of the Delaware Department of Corrections facilities. Through a partnership with Community Oriented Correctional Wellness Services (COCHS), Connections is maximizing continuity of care by connecting individuals in correctional facilities with providers in the community. The system brings providers into the facilities that the inmate can also connect with for intendance afterward being released. Approximately 25,000 inmates cycle through Delaware's correctional facilities annually and, on average, Connections works with about 7,000 prisoners per day.35

Expanding wellness coverage among the criminal justice-involved population may contribute to offsetting savings for states. Although the Medicaid inmate exclusion policy limits Medicaid payments for almost health care services provided to individuals while incarcerated in prison or jail, Medicaid reimbursement is available for intendance provided to eligible individuals admitted to an inpatient facility, such as a hospital, nursing home, or psychiatric middle. Prior to the ACA, only a few states had pursued Medicaid reimbursement for these services given the express share of the incarcerated population that could authorize for Medicaid. However, those that did pursue federal matching dollars for inmate inpatient services demonstrated state savings.36 The Medicaid expansion offers greater potential savings to states from reimbursement for inpatient services provided to incarcerated individuals, since a larger share of the incarcerated population may qualify for Medicaid and because the federal government is providing states an enhanced federal matching rate for newly eligible adults. Several states have projected substantial state savings from obtaining Medicaid reimbursement for inpatient care provided to prisoners.37 Increased coverage amidst the formerly incarcerated population as they return to the community may also contribute to other state and local savings through reductions in uncompensated intendance and savings in other indigent intendance programs.

Conclusion

Individuals moving into and out of the criminal justice population are a low-income population with significant physical and mental wellness needs. Historically, this population has had loftier uninsured rates and very limited access to Medicaid coverage given the programme'due south limited eligibility for adults prior to the ACA. The ACA'south Medicaid expansion and Marketplaces, coupled with targeted outreach and enrollment efforts, provide opportunities to increase coverage amid this population that should help to improve their ability to admission needed intendance and contribute to greater stability in their lives and reduced rates of recidivism. States expanding Medicaid may also reduce spending for their incarcerated population and accomplish other state and local savings stemming from gains in coverage through Medicaid and the Marketplaces among formerly incarcerated individuals who are returning to the customs.

Source: https://www.kff.org/uninsured/issue-brief/health-coverage-and-care-for-the-adult-criminal-justice-involved-population/#:~:text=Correctional%20facilities%20are%20required%20to,and%20types%20of%20correctional%20facilities.

Posted by: anayadoingunt.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Do Correctional Facilities Required To Provide Health Services To Incarcerated Individuals?"

Post a Comment